Kurumunuzdaki Yetenekleri Keşfetmek için Bilimi Kullanın (I)

Using Science to Identify Future Leaders:

Part I – Introducing the Concept of Learning Agility

by Kenneth P. De Meuse, Ph.D.

Some sobering statistics on leadership

- In an extensive review of the literature, it was found that on average 50% of managers fail (Hogan, Hogan, & Kaiser, 2011).

- In a series of studies, researchers at the Center for Creative Leadership observed fully one-third of all senior executives derail (Leslie & Van Velsor, 1996).

- A recent survey of 200 companies revealed that only 17% of executives were satisfied with their organization’s accuracy of identifying high potential talent (Karakowsky & Kotlyar, 2011).

- A recent meta-analysis revealed the relationship between leader success and personality scores was r=0.22, which translates in to accounting for less than 5% of the variance (Schmidt, 2013).

Many companies – indeed most companies – have trouble attempting to identify and develop their future leaders. For many, it’s not a matter of effort. They dutifully go through their annual ritual of obtaining a list of possible high potentials from upper-level executives, carefully examine their performance records, review their strengths and developmental areas during the talent review sessions, then ensure they have opportunities to grow during the coming year. A tremendous amount of time, effort, and money. All those resources! Yet, it seems these companies would have just as much success tossing dice. For other companies, there appears to be little strategy at all – when a leadership hole appears, they simply plug it with an outside hire or toss someone in who is ill-prepared to assume the role. Annual talent reviews end up as “replacement planning” more than “succession planning.” But why is this? Why can’t companies do a better job identifying and developing their high potential talent?

Typical Approaches to Identifying High Potentials

One of the key indicators companies use to identify high potential talent (“HIPOs”) is previous job performance. And, indeed, performance can serve as an important source of information. It should not be the only source, however. One of the basic tenets of psychology is that “the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior.” We need to remember that a fundamental assumption of this tenet is that the future situation will be the same as the past one. When an employee is promoted, this is no longer the case. The newly promoted situation most times is quite different, with new tasks, responsibilities and job duties, new colleagues, and a new boss. Former behaviors may not be predictive at all. New competencies, new patterns of behavior, and different leadership approaches frequently are required. A survey conducted by the Corporate Leadership Council found that only 29% of high performers actually were high potentials (2005). Thus, if one uses only past performance to select high potential talent, one will be wrong 7 out of 10 times. Those odds are worse than flipping a coin. Another sign organizations often employ to identify HIPOs is to reward good company soldiers. One may hear that “Jerry is loyal, always volunteers for extra assignments, and gets along with everyone.” That he “has chaired the United Way campaign for the past five years.” That “customers love him.” All those compliments are wonderful. It demonstrates that Jerry is dedicated to the firm, highly engaged in his work, and has terrific interpersonal skills. However, does it make him a high potential? Does it suggest that he will perform well in a new job? Or, for that matter, does it suggest that Jerry even wants to be promoted away from a job he loves? The sports world is full of stories of highly talented ballplayers who fail miserably as coaches and general managers.

There are two other factors many organizations often utilize to identify high potential talent: employee visibility and the “similar to me effect.” Talent management professionals need to understand that in most companies a highly restricted number of employees has regular interactions with senior leaders. Soliciting the input from executives for their recommendations of HIPOs severely limits the talent pool. Further, who are the individuals they are most likely to nominate? Employees who are similar to them. Psychological research for decades has demonstrated that we all have perceptual biases and tend to evaluate others more favorably when they are similar to us (Pulakos & Wexley, 1983). Thus, such an approach perpetuates the company’s demographic composition of its leaders, limiting diversity in the HIPO talent pool. It is critical to the future of the organization that its next generation of leaders represent the workforce and the marketplace of tomorrow, not the past.

Learning Agility – A Better Way

One of the best titles for a leadership book was written by Marshall Goldsmith. In his What Got You Here Won’t Get You There (2007), Goldsmith emphasizes the notion that successful leaders understand they need to perform differently and develop new competencies when promoted. They recognize that the behaviors which caused them to be effective previously will not automatically translate to success in their new roles. Morgan McCall, Mike Lombardo, and Ann Morrison were the first researchers to note it in their seminal book entitled, The Lessons of Experience (1988). And that was more than 25 years ago. These researchers examined why executives had succeeded or derailed and discovered a key determinant was related to an individual’s ability and motivation to learn from experiences. Successful executives learned more effectively. They were willing to leave their comfort zones, take risks, and learn from their mistakes. They also were able to apply that learning and were sufficiently flexible – agile – to perform differently in new organizational environments.

A decade later, Mike Lombardo and Bob Eichinger (2000) coined the concept of learning agility to help describe those individuals who had the potential to successfully navigate the newness of promotions. Since that time, several other authors have written about the importance of modifying one’s behaviors and leadership competencies as individuals climb the corporate ladder. Sydney Finkelstein discussed it in Why Smart Executives Fail (2003). So did John Zenger and Joseph Folkman in The Extraordinary Leader: Turning Good Managers into Great Leaders (2002).

The term “learning agility” captures the essence of this phenomenon. It can be defined as the ability and willingness to learn the right lessons from work experiences and then apply

those lessons to perform well in new and challenging leadership situations (see De Meuse, Dai, & Hallenbeck, 2010). Organizations around the globe such as Siemens, Novartis, Canon, Pfizer, and Delphi are employing the construct to help them identify and develop their HIPOs.

Many companies use a 9-cell matrix similar to the one below to describe talent. On one axis is performance. On the other axis is potential.

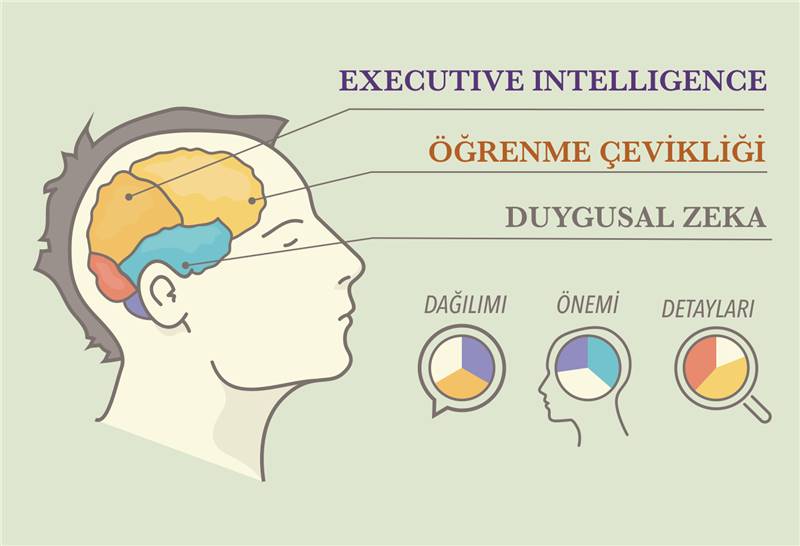

During the annual talent review session, employees are discussed in terms of both past performance as well as future potential. This structure provides a meaningful dialogue that examines an individual’s leadership potential independently of job performance. It is best to calibrate job performance for three years rather than simply how the employee performed during the past year. Such a sustained performance metric eliminates performance peaks and valleys due to conditions that may be beyond the employee’s control.

Three different factors should be considered when evaluating an individual’s potential. First, discuss the personal characteristics the employee possesses (e.g., career ambition, drive, intelligence, willingness to relocate, and so on). These attributes are largely stable for an individual. Second, review the work-related experiences the employee has encountered. Has he or she been exposed to different bosses, job functions, organizational cultures, and/or a diversity of employees? Has he or she led a committee, performed a challenging assignment, or even failed on a project? Such activities develop leadership skills and other important competencies.

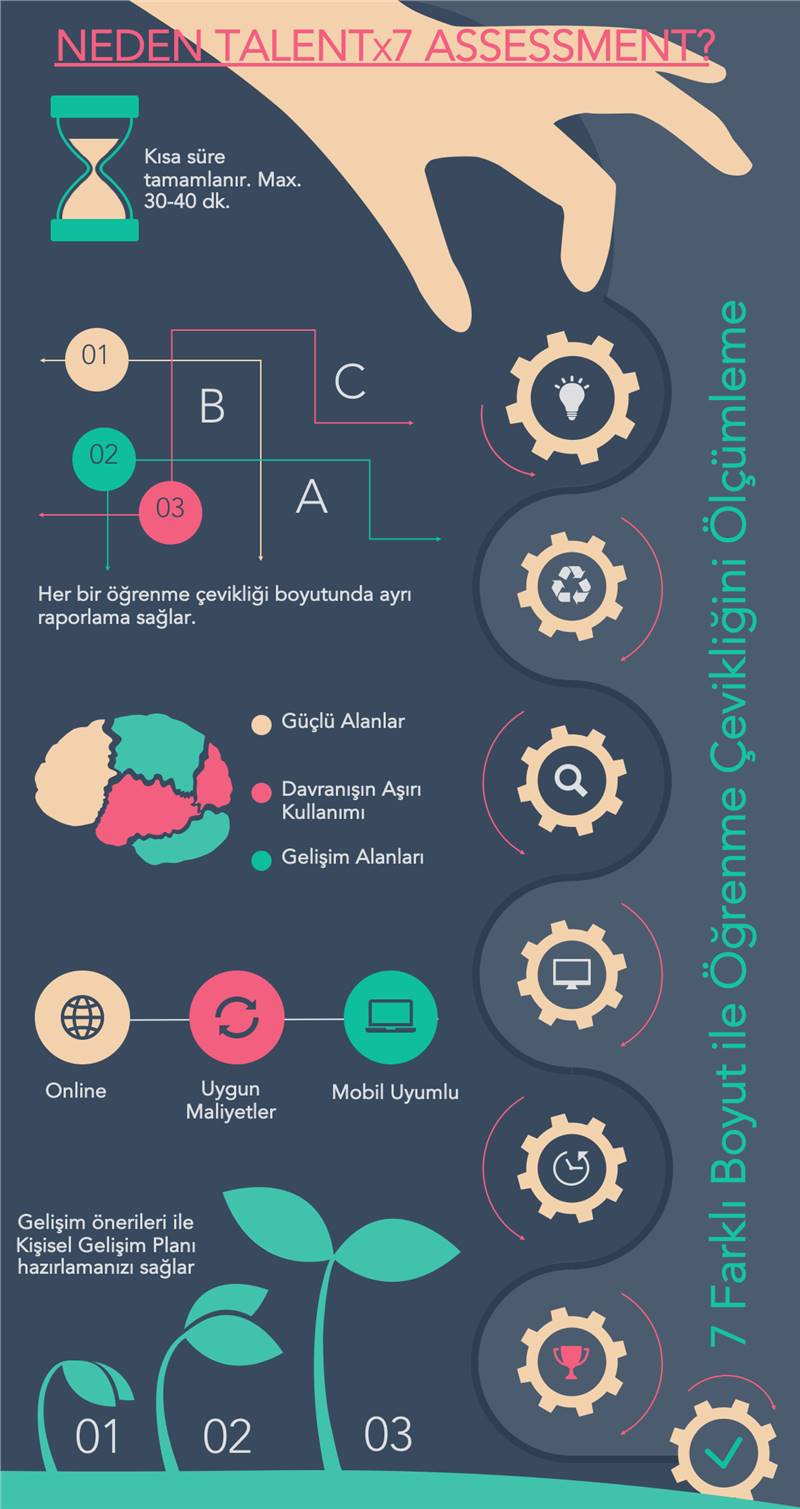

The last and primary factor influencing leadership potential is learning agility. In brief, learning agility provides a window into an individual’s capacity to learn from experience and the flexibility to behave differently depending upon the needs of the situation. The additional clarity that a measure of learning agility brings to the talent review process when discussing an employee’s potential cannot be overstated.

Learning agility enables an organization to assess leadership potential objectively, quantitatively, and scientifically. The impact of personal relationships, organizational politics, and individual biases are minimized in the talent discussion. Limited interactions are not overblown. Vocal advocates supporting the candidacy of their “golden boy or girl” receive no more consideration than quiet supporters of an unfamiliar individual. Gender, race, and other irrelevant personal characteristics are discarded. Rather, an individual’s learning agility score is examined within the context of a meaningful, scientifically validated predictor of leadership potential. Moreover, scores on various subscales of learning agility pinpoint leadership weaknesses that should be developed during upcoming job assignments and training.

According to Goebel and Baskerville (2013), learning agility is one of the single most important predictors of leadership success today. It is becoming the cornerstone for identifying and developing high potential talent. Two recently published empirical studies directly investigated learning agility, high potential talent, and leadership success. Dries, Vantilborge, and Pepermans (2012) measured job performance and learning agility in seven different organizations. They found that both performance and learning agility were statistically related to being identified as a high potential. They discovered high performing employees were three times more likely to be identified as a high potential than employees with low performance. However, they found that being high in learning agility increased an employee’s likelihood of being identified as a high potential by a factor of 18. The researchers concluded that “learning agility is an overriding criterion for separating high potentials from non-high potentials” (Dries et al., 2012, p. 351).

My colleagues Guangrong Dai and King Yii Tang and I recently conducted two separate field studies – one cross-sectional and one longitudinal – to investigate the empirical linkage between learning agility and leadership success. In Study 1, we found learning agility was significantly correlated with the following two objective indices of career outcomes: (a) CEO proximity and (b) total compensation. This study also found a positive relationship between learning agility and ratings of leadership competence. In Study 2, we observed that learning agility was significantly related to career growth trajectory. High learning agile individuals were promoted more often and received higher salary increases than their low learning agile counterparts during a period of 10 years. Thus, in the dynamic business world of today, a leader’s success seems largely dependent upon his or her ability and willingness to learn, grow, and respond flexibly. The concept of learning agility scientifically captures this characteristic.

Conclusion

More than a decade ago, it was estimated that the price of a derailed executive can be as high as $2.7 million (Smart, 1999). The cost certainly has increased since then with escalating executive salaries and shrinking talent pools. More importantly, the hidden costs of failed leadership in the form of unmet business objectives, lost clients, and disengaged employees are nearly impossible to calculate. Bad management at any level causes a number of organizational problems. A goal of talent management is to minimize such mistakes and ensure that the right candidates are selected and developed for tomorrow’s leaders. Traditional performance-based approaches for identifying and developing future leaders need to improve. The careful and strategic application of learning agility offers organizations a highly reliable, scientific way of increasing the chances of being successful.

In Part II of this whitepaper, I will investigate how we can measure the learning agility construct.

References

Corporate Leadership Council. (2005). Realizing the full potential of rising talent. Washington, DC: Corporate Executive Board.

Dai, G., De Meuse, K. P., & Tang, K. Y. (2013). The role of learning agility in executive career success: The results of two field studies. Journal of Managerial Issues, 25, 108-131.

De Meuse, K. P., Dai, G., & Hallenbeck, G. S. (2010). Learning agility: A construct whose time has come. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62, 119-130.

Dries, N., Vantilborgh, T., & Pepermans, R. (2012). The role of learning agility and career variety in the identification and development of high potential employees. Personnel Review, 41, 340-358.

Finkelstein, S. M. (2003). Why smart executives fail: And what you can learn from their mistakes. New York: Portfolio.

Goebel, S., & Baskerville, R. (2013, September). From self-discovery to learning agility in senior executives. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Engaged Management Scholarship (pp. 1-19), Atlanta.

Goldsmith, M. (2007). What got you here won’t get you there: How successful people become even more successful. New York: Hyperion Books.

Hogan, J., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2011). Management derailment. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 555-575). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Karakowsky, L., & Kotlyar, I. (2011). Think you know your high potentials? Canadian HR Reporter, 24(21), 23.

Leslie, J. B., & Van Velsor, E. (1996). A look at derailment today: North America and Europe.

Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Lombardo, M. M., & Eichinger, R. W. (2000). High potentials as high learners. Human Resource

Management, 39, 321-330.

McCall, M. M., Jr., Lombardo, M. M., & Morrison, A. M. (1988). The lessons of experience: How successful executives develop on the job. New York: The Free Press.

Pulakos, E. D., & Wexley, K. N. (1983). The relationship among perceptual similarity, sex, and performance ratings in manager-subordinate dyads. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 129-

139.

Schmidt, F. (2013). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 95 years of research findings. Presentation made at Personnel Testing Council of Metropolitan Washington (PTCMW) fall event. Washington, DC.

Smart, B. D. (1999). Topgrading: How leading companies win by hiring, coaching, and keeping the best people. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Zenger, J. H., & Folkman, J. R. (2002). The extraordinary leader: Turning good managers into great leaders. New York: McGraw-Hill.

About the Author

Dr. Kenneth P. De Meuse is founder and president of the Wisconsin Management Group, a consulting firm specializing in leader identification, executive coaching, and research on high potential talent. Dr. De Meuse is a global thought leader on the assessment and development of leadership, and has presented his research on learning agility and leadership competencies at numerous professional conferences, including the Academy of Management, American Psychological Association, Society for Human Resource Management, The Conference Board, International Coach Federation, Society for Consulting Psychology, and the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. His 2010 journal article on learning agility is considered the first scholarly publication on the construct

and lays the foundation for its scientific exploration.

Throughout his career, Dr. De Meuse has consulted on a variety of strategic and leadership issues at businesses such as Nestle USA, Lucent Technologies, Siemens, RMS McGladrey, Presto Industries, and Ayres Associates. Prior to establishing the Wisconsin Management Group, he was executive vice president of Research and Product Development at Tercon Consulting, a global consulting firm headquartered in Washington, DC. He also was vice president of Global Research at Korn/Ferry International for six years. In addition, Dr. De Meuse was on the faculties of Iowa State University and the University of Wisconsin (Eau Claire). He has published more than 50 peer-reviewed journal articles and authored five books.

Dr. De Meuse earned his Ph.D. in Industrial/Organizational Psychology from the University of Tennessee and his Master’s degree in Psychology from the University of Nebraska. In acknowledgement for his contributions to the science and practice of talent management, he was elected Fellow by the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.